September commonly symbolizes a few different things for people. If you’re a parent and exhausted from attempting to keep your kids occupied during the summer months, September equates to Back to School for you and a bit of normalcy to your schedule. I have a few moms at the studio who are cheering for the summer to arrive in Mid-April, only to have them in full agreement by the 4th of July that Mid-August and school can’t come soon enough. If you’re a sports fan, specifically a football fan, September and the fall months mean football season for you. For those who have been stumbling through their fitness program for the last sixty days, September just feels like the right time for a reset. If you’re one of those people, there’s psychology behind why you may feel this way.

Behavioral scientists describe the September effect as part of the “fresh start effect,” when life transitions feel like natural opportunities to begin again. The start of a school year, a new season, or even a new month can provide a psychological boost that motivates people to recommit to routines. In Las Vegas, as the heat begins to break, it inspires outdoor activities. Bike rides, hikes, and brisk walks after dinner start to emerge on the schedule for many. Summer schedules tend to be a bit looser, autumn brings routine back to the calendar, sharper routines, and an overall sense of renewal. The 100 days between mid-August and Thanksgiving tend to be the busiest at the studio. It’s not uncommon for me to see someone go on vacation in June and then watch them struggle to get back to the gym until late August and early September. If you fall into that category, here are a few tips to help you get back on track.

Like January, don’t try too much at once. Going back to five days a week of training after a couple of months of inactivity is setting you up for failure. Start with two to three days a week. Discipline is a muscle, and you’ll need to build it back up. Trying to do too much at once can lead to excessive muscle soreness and D.O.M.S (delayed onset muscle soreness). Struggling to get out of the car and upstairs is a great way to demotivate yourself. Remember Rome wasn’t built in a day, so take your time and ease back into a routine.

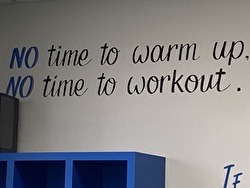

Once you walk through the door of the gym, don’t blow off your warm-up. I have a quote on our wall at the studio, which I point to when needed- “No Time to Warm up, No Time to Workout.” Foam rolling, soft tissue work, and mobility drills aren’t only beneficial towards your workout and performance, they help you avoid injuries. The last thing you want to experience in your first week is a strained calf muscle or cranky lower back. It’s the person who hasn’t been training that needs a good warm-up the most. Warm-ups are not meant to entertain or impress; just do them.

You can’t out train a poor diet, so part of the autumn reset is getting your nutrition back in order. The fourth of July is past, so put down the hotdogs and get back to lean cuts of protein, whole grains, and vegetables. I’m agnostic to specific diets, I approach it like I approach training. It must be personalized to you. Vegan, keto, paleo, and intermittent fasting, they all work and can produce benefits. It matters on the person. I like to keep it simple and address hydration first. Make sure you are getting in enough water. I was able to attend a lecture this summer from certified clinical nutritionist, Robert Yang. He recommends drinking half your body weight in water daily. That means a 200-pound male should drink 100 ounces daily. To avoid getting up throughout the evening to urinate and disrupt your sleep, he suggests front loading your water. Immediately after rising in the morning drink 25% of that daily intake, or 25 ounces for this example. During and around exercise consume 50% of your daily intake (50 oz), leaving 25% to be consumed with meals and throughout the day.

Finally, the colder weather and busy schedules during fall often coincides with higher rates of colds and flu. Exercise is one of the most effective tools to strengthen immunity. Moderate activity such as brisk walking, cycling, or strength training improves circulation of immune cells, helping the body respond more efficiently to pathogens. For example, someone who walks for 30 minutes five times a week may experience fewer respiratory infections than someone who is sedentary.

September feels like a clean slate, and science explains why this moment fuels motivation. The season offers both external triggers and internal drive to create meaningful change. By avoiding common mistakes, setting realistic goals, easing back into it, and prioritizing nutrition, exercisers can use the September reset as a springboard to lasting success.