Physical work is good. Our bodies are built on it. “Tissues of the musculoskeletal system have a common denominator: they all require the stimulus of nondestructive stresses to maintain their health.” This is taken from Mechanical Low Back Pain, Perspectives in Functional Anatomy by James Porterfield, and Carl DeRosa. One of the first things that I explain to someone when I start to work with them is that you are going to work. It’s my job and responsibility to determine the correct dosage, but once we figure that out, it’s time to sweat. On that note, like a kid visiting Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, too much of a good thing is not good for you either.

I take program design seriously. There is a reason behind everything we do at the studio. It starts with our warm-up/tissue work, then the movement prep exercises, mobility, strengthening drills and our metabolic conditioning. There is a reason for everything. We don’t follow the common fitness misnomer that if it makes you tired, it must be good. The key is to challenge the system just enough. In my last post, I mentioned how our internal barometer has been skewed, due to the minimal physical stress placed upon our bodies in the current era. I think we all know someone who will save a trip walking in the parking lot at Target for a case of bottled water and opt to have it delivered to their door via Amazon.

Assessments minimize the risk of injury. Heart monitors and observing someone’s perceived rate of exertion (PRE) allows us to determine someone’s work capacity. The research is solid. It’s safe to assume that one of the contributing factors to maintaining musculoskeletal health is activity that places a controlled stress on the tissues (ligaments, tendons, muscles). By comparison, immobilization has a negative effect on the musculoskeletal tissues. Can anyone say quarantine?

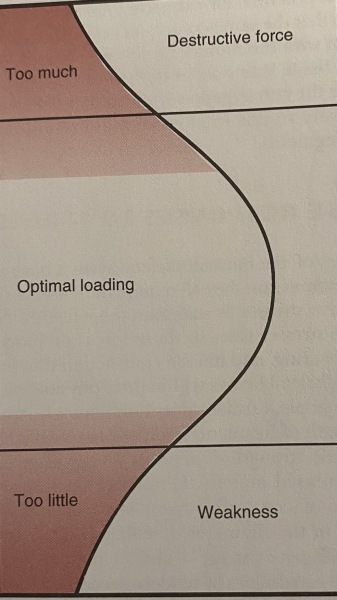

The trick is to apply the right dosage. In my world of strength and conditioning, we reference this as the optimal loading pattern. This can be the movement pattern, load being applied, and for how long, or duration. To clarify my point, the illustration below provides a visual explanation. There is a point where too little load creates weakness, optimal loading creates optimal health, and then there’s excessive load, or overuse. This is where tissue breakdown can happen.

The obvious thought is that too much load can cause injury, but did you consider too much volume? As cited, by Porterfield and DeRosa:

“Tissue breakdown may also occur with prolonged, excessive overloading, such as seen with overtraining or cumulative microtrauma. “

I have wrestled with this up close and personal as I have dealt with injuries accumulated from 30 years of coaching. It was my own naivete, that I misjudged the physical toll demonstrating exercises 8-12 hours a day, 5-6 days a week, for 30 years would play on my body. A lot older and a little wiser, I now keep a mental record of how many times I demonstrate a lunge or squat throughout the day. Like the flooring guy who works on his knees for twenty years, to be later diagnosed with knee trauma, it’s not the single action that caused a problem, but the prolonged activity. This is why having a coach is valuable. We all need a skilled person in our corner who can tell us when we need to push a little more, and then pull us aside when we have had enough.

I’ll see you at the studio.