We are all different. Our emotional, physical, and mental make-up is unique to each of us, but there also exists commonalities amongst us. Have you heard the saying, “same, but different”? Regarding gaining strength, there are five factors you should consider, with some of these factors, you could lump many of us in the same bucket, and others you can have multiple groups. I wanted to clarify how you can expose a group of people to a similar strength program and get different results.

Trainability- This refers to the potential to improve and build strength in response to a specific training program and depends largely on genetic factors and pre-training status. Genetic factors determine the potential for hypertrophy, the leverage characteristics about each joint, the amount of fast and slow twitch fibers within each muscle group, and metabolic efficiency. I see this a lot when a married couple joins our studio. They are exposed to the same program. Their exercise frequency is similar, because they train together, and yet will experience different results. As stated by Mel Siff PhD in his benchmark book Supertraining, “Moreover, during long-term training, the blood serum levels of biologically active unbound testosterone may also be of importance for trainability (Hakkinen, 1985).” Simply put, the genes from your mom and dad, whether you like or not, affect your trainability and play a role in how you progress at the gym.

Neuromuscular Efficiency- This refers to the skill with which one performs a given movement and relates to how efficiently and intensively one engages muscle fibers in the appropriate muscle groups to produce the movement pattern accurately and powerfully. I believe this can be affected by the quality of coaching. Proper exercise progression is key. All motor action is controlled by nervous and neuromuscular processes. In this, I see many similarities among people. Teaching people how to move properly, and not overwhelming them in the process, can generate similar outcomes.

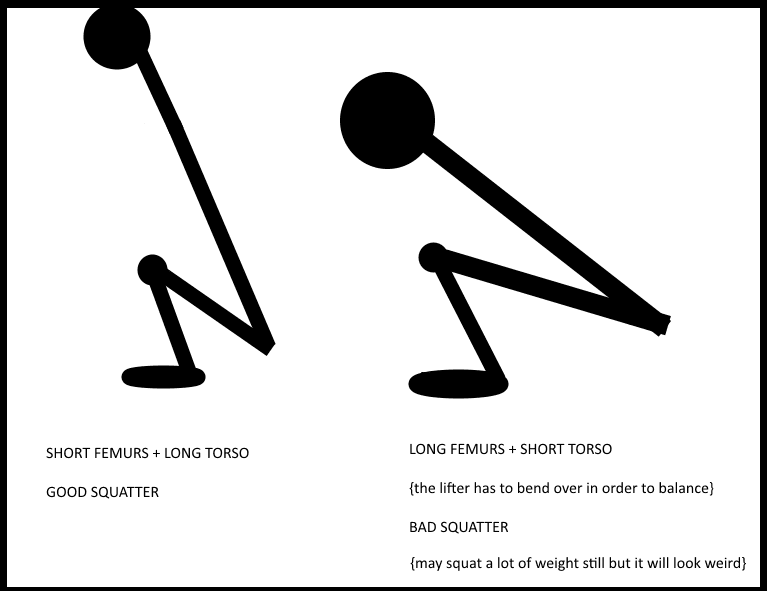

Biomechanical Efficiency- This factor also relates to genetics, such as the leverage characteristics of the body. There is a reason basketball players tend to have problems with squats. Their long levers put them at a disadvantage. If you watch the power production of a discus thrower or golfer, a longer lever or limb length will produce more force.

Psychological Factors- I could author an entire thesis on this one. Training performance depends heavily on psychological factors such as motivation (to achieve specific goals), aggression, focus and concentration, the ability to tolerate pain or to sustain effort, the ability to handle anxiety or stress, learning ability, the current mood of the participant, the ability to manage distractions, and the ability to relax effectively. Functional and movement training brought this to the attention of the strength and conditioning industry once we started to migrate off machines to free-weights, kettlebells, and the like. Go to a local “big box” gym and watch a person perform a set of leg extensions while on their phone. You don’t have to be in a performance lab to determine their focus on the movement may be minimal.

In some people, muscle burn or the anticipation of it will cause them to stop. In our studio, we will adjust exercise selection based upon the person's ability to learn. To avoid the feeling of overwhelm, we will keep some movements basic for some to achieve a better training stimulus. Mood is also a key component. Just take a moment and reflect on this. Have you experienced a workout when you just wanted to get it over, you could care less about how much you were lifting or for how long, compared to days you were more focused on what you were doing and more engaged in the workout? The psychological factor is also on a sliding continuum. It’s constantly changing. When I’m hiring coaches, their ability to work with people and communication skills far outweigh what they currently know about exercise.

Pain and Fear of Pain- This factor piggybacks on the previous factor of psychological. I should clarify that when I’m referring to pain in this instance, I’m referring to pain of effort or pain of fatigue.

“The pain of effort is not necessarily a result of injury but refers to one’s personal interpretation of the intensity of a given effort and is sometimes assessed on a subjective scale called the rating of perceived effort (RPE).” Mel Siff PhD, Supertraining

This is also where the fitness industry did a poor job in their marketing in past years to the novice or beginner. People join my studio all the time expecting to be beaten up. They’ve heard the mantra, “No pain, no gain.” I try to explain that to make the positive changes they desire, there must be a level of challenge. It’s important to share that it should be an achievable challenge. That challenge may be pulling most of your bodyweight in a row using the TRX suspension system, or intensely pedaling on the Assault bike. At the end of the day, I’ll stick by one of my favorite sayings: It will not change you, if it doesn’t challenge you.

I’ll see you at the studio.